The Uniquely American Shopping Mall Experiment

How a staple of American culture - and suburban post-war capitalism - has left dozens of abandoned concrete husks to litter our neighborhoods, and how they were set up to fail from day 1.

The American mall is dead. On life support, at least. In order to find out why, we can turn to an informative source that provides us an exemplary case - 1980’s The Blues Brothers.

In case it wasn’t evident, this scene was actually set and filmed in a real mall. Situated in the township of Harvey, Illinois, a declining rust belt southern suburb of Chicago, Dixie Square Mall was a typical suburban indoor shopping mall. Built in 1964 and opened in 1966, Dixie Square boasted an occupancy of 64 interior stores and 6 anchor stores, making it one of the largest malls in the country at the time. Most major American chains you think of when you think mid-20th century were present - JCPenney, Montgomery Ward and Woolworth included (Sears, a Chicago-based company, already had stores in the area), plus even the midwestern staple Jewel-Osco.

While Dixie Square was an early example of the mega-mall, Harvey was also a relatively early example of midwestern rust belt decline. A small city, Harvey’s economy was largely dependent on the factory of Buda Engine Company, producing engines for small vehicles (like tractors). The city’s population was largely a mix of working class folks just above or just below the poverty level, and was more than half nonwhite - which is not often a demographic you often see targeted by brand new, suburban upscale shopping centres like Dixie Square. The opposite, in fact.

As time went on, various stores closed their doors, most of them citing the same arguments you hear now - crime and shoplifting, though the crime rate in the area around the mall was not higher than surrounding areas with more successful malls. Montgomery Ward closed their Dixie Square location in 1976, followed by Jewel, Turn Style (a discount clothing store owned by Jewel), Woolworth, and Walgreens doing so in 1977. In November 1978, the mall (having been rebranded to just “Dixie Mall” in a last-ditch PR campaign), closed its doors after having only been open a total of 12 years. JCPenney remained open an extra two months before closing after the first of the year.

Pretty much immediately, the building was leased out to the school district for use as a temporary location for the local high school. In mid-1979, The Blues Brothers was filmed here, the last time the building would at least look like a bustling shopping mall. (The local school district would go on to sue Universal Pictures for not doing any cleanup work in the mall after filming this segment.) By New Years’ 1982, all the tenants of the mall, permanent and temporary, were gone, and the building was abandoned.

Dixie Square Mall, a multimillion dollar project that had been designed to revitalize a local economy for decades in the future, had been in use for 15 years and 2 months before being abandoned, making it one of the very first examples of an abandoned mall.

It would stand as an abandoned husk, having some smaller parts demolished, individual areas of roofs collapsing, vandalized, and being set on fire numerous times of varying severity, until it was eventually demolished on May 17th, 2012. The mall had sat abandoned for 30 years and 5 months - more than twice the amount of time it was actually in use, and nearly 3 times longer than it was an active mall.

This is not a unique example among American shopping malls - just a very early one.

The Boomers Caused This (kinda)

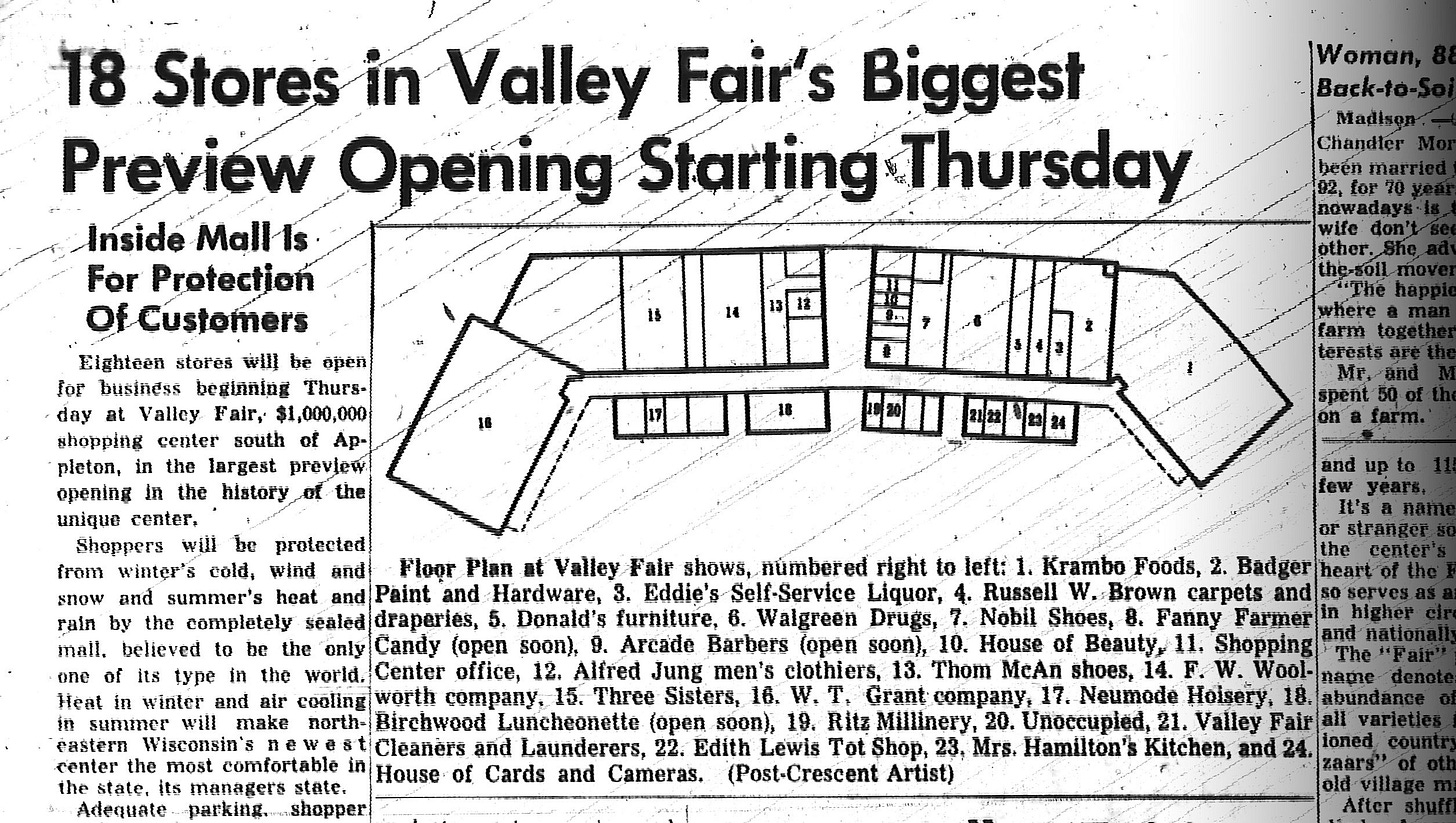

Probably unsurprisingly, the rise of the suburban enclosed shopping centre can be tied to the rise of the American suburb. The development of the suburb in the post-WWII period has been thoroughly documented and studied elsewhere, but what matters here is that after the suburbs were developed, the newly minted families in their freshly built cookie-cutter redlined single-family detached homes needed somewhere to shop for things like appliances and clothes, and thus was the nexus of what we consider the modern shopping mall. Valley Fair Shopping Center, in Appleton, Wisconsin, was the first example of the modern enclosed shopping mall, opening in 1955.

Appleton was actually not a modern new-build suburb. It was, however, a sundown town until 1970.

Valley Fair would be on the downswing by 1984, losing ground to malls in nearby new-build suburbs. It would be demolished in 2007.

The San Francisco 49ers Did This (sorta)

One of the most prominent mall developers in the United States was The DeBartolo Corporation, a Youngstown, Ohio company owned by Edward DeBartolo. He had been an early proponent of the strip mall design beginning in the late 1940s, and had entered the enclosed shopping mall business with the opening of Glen Burnie Mall in Maryland in 1964. (The modern day DeBartolo Development company actually credits DeBartolo with the idea of the enclosed shopping mall, which is seemingly false.)

What DeBartolo would pioneer, however, is the megamall. In 1969, US Steel Corporation decided that they would take a slag heap alongside an empty, rural stretch of PA Route 51 about 25 minutes outside of Pittsburgh, clear it, and offer it for development. In 1976, USS partnered with DeBartolo in order to plan and develop a three-story, 1.6 million square foot, 200 store, 6 anchor mall in a largely undeveloped suburb of Pittsburgh, hoping to attract enough business to create a large amount of development nearby to complement it. Century III Mall, named to commemorate America’s third century, would be the largest mall on the east coast, a title it would have until Aventura Mall1, also developed by DeBartolo, opened in Miami in 1983.

The DeBartolo Corporation was taking a significant risk in proposing such a monstrous development. They would eventually find a way to secure a steady income even if any of their shopping mall prospects failed - DeBartolo purchased the San Francisco 49ers in 1977. (He also purchased the Pittsburgh Penguins that same year, though at the time they were far more of a revenue pit than a stream. This would remain true until the drafting of Mario Lemieux in 1984.)

Century III would open to fanfare in 1980, and would remain a staple of the Pittsburgh area for years to come. The mall would be continually maintained and updated with brand new stores and brand new interiors - including an expensive remodel in 1996 that removed an area in the centre court modeled after the so-called “conversation pit” often seen in mid-century homes.

In 1999, an upscale outdoor shopping district known as The Waterfront would open just 10 minutes away from Century III. It sported more niche and luxury brands than you’d find at Century III, and even had a state-of-the-art Loews cineplex. (While mall cinemas had been a relatively common feature in some malls, Century III would not have one, nor would any Pittsburgh-area mall until 2005). It also featured big box stores like Target and grocery stores like Giant Eagle, which made it a much more attractive option to the residential areas surrounding it - which happened to be those closest to Century III.

Two other Pittsburgh area malls would undergo major renovations around the same time - South Hills Village in 1999 and Ross Park Mall in 2000 - modifying their retail model to be more focused on having a wider selection of specialty stores dedicated to major luxury & name brands.

This model of shopping mall, as well as outdoor centres like the Waterfront, are excellent case studies in the two strategies taken by malls to ensure their success into the new millennium. Century III, however, would gradually lose all of its anchor stores, which in turn drove away most foot traffic, which then drove away all the smaller stores. The mall would be deemed unsafe by West Mifflin Township on February 6th, 2019, which would then turn into permanent closure on February 16th. The mall remains abandoned to this day, having been set on fire a couple times in the process. No viable redevelopment plans have been announced as of yet, at this point it mostly seems to just be a way for the West Mifflin Police to file easy felony trespassing charges against teenagers.

DeBartolo, through various projects and corporate acquisitions, would eventually become the largest mall owner in the United States, at one point owning 10% of all mall space in the world. DeBartolo would die a billionaire in 1994, and his DeBartolo Realty Corporation would be bought by Simon Property Group in 1996. For posterity, here’s a partial list of malls developed (not acquired) by this company that was once worth a billion dollars:

Glen Burnie Mall, Glen Burnie, MD (closed 2018)

Woodville Mall, Woodville, OH (closed 2011)

Richmond Mall, Cleveland, OH (closed 2021)

Century III (closed 2019)

Eastern Hills Mall, Harris Hill, NY (open, currently being redeveloped)

Southern Park Mall, Boardman, OH (open, partially redeveloped in 2021)2

Great Lakes Mall, Mentor, OH (open, renovated into an upscale mall in 1988. There’s a Round1 here, that’s what kind of mall it is)

Summit Mall, Akron, OH (open, renovated into an upscale mall in ~2004)

Lafayette Square Mall, Indianapolis, IN (closed, redeveloped 2022)

Upper Valley Mall, Springfield, OH (closed 2021)

Brunswick Square Mall, East Brunswick, NJ (open, high vacancy rate)

Chautauqua Mall, Lakewood, NY (open, high vacancy rate)

Miami International Mall, Doral, FL (open, originally developed as an upscale mall)

Lima Mall, Lima, OH (open, high vacancy rate)

Raleigh Springs Mall, Memphis, TN (closed 2016)

Randall Park Mall, Cleveland, OH (closed 2009)

Castleton Square Mall, Indianapolis, IN (open, renovated into an upscale mall in ~1998)

Cheltenham Square Mall, Philadelphia, PA (redeveloped 2018)

What we see here is a pretty clear picture - redevelop or die. What we also see is millions of dollars worth of materials and millions of acres of land that could have been used for…anything other than this, instead being left to rot, providing no purpose to the neighboring communities, using up land that could be (and in a lot of cases has since been!) used for things like housing.

DeBartolo Development has since entered the housing market, ranging from new-build affordable housing to luxury townhouses in renovated city high-rises. At least it’s something, I guess.

How the Convenience of Capitalism Sunk the Mall

Around the same time malls hit their peak number in the mid-1980s, another shopping phenomenon was on the rise - Walmart, or the concept of big-box retail in general. Again, there exists countless amounts of academic material covering the societal and economic factors that caused companies like Walmart to experience such success, so I’m instead going to focus on the mall aspect of it.

One of the defining features of American capitalism is an insistence on convenience (or laziness, however you prefer to describe it). Having all of the stores you needed to go to in one very large shopping complex was a huge stride forward in that department, particularly for people in car-dependent suburbs - you could do all your shopping in a single day trip and be home in time to make your husband a glazed ham encased in gelatin.

As time passed, however, the the average American lifestyle changed. Former housewives entered the workforce, baby boomers became teenage boomers and adult boomers, we had a couple recessions there, cost of living was up - basically, the average American had less free time than they did in the 1950s and 60s. The shifts in lifestyles created a new concept - instead of having a bunch of stores selling everything you’d need under one roof, what if we compacted that into one store where you could buy a hunting rifle, condoms, and Levi’s without so much as walking through more than one set of doors?

Immediately, the dawn of a new age of American commerce was upon us, as Americans were immediately entranced by this concept. Since the concept inherently took up less space than a full blown shopping mall, it meant that it could be positioned much closer to existing population areas, meaning easier access for consumers. They also would spend much less time walking from store to store, and only had to go through one checkout at the end. The only extra stop you had to make was at the grocery store - which was also true of shopping malls, for the most part, and by the early 2000s, it would not even be true of most Walmart stores anymore.

This concept was outright incompatible with shopping malls. The vast majority of the other stores inside the mall would just be competing with your business, for one, plus Walmart prefers purpose-built stores based on their own designs and floorplans. There were some exceptions to this, but few and far between, and in the US most of them vanished by the mid-2010s, either due to the mall closing or the Walmart relocating.

(Some countries, namely Canada, would see success with the Walmart-in-a-mall format, but most countries also do malls differently than we do.)

The rise of big-box retail is often credited with the decline of small businesses in America - which is true, to some extent - but it isn’t as often credited with the decline of the megamall, functionally the exact opposite of local American business. Big box retail left a path of destruction in its wake really unlike any other until the rise of Amazon - which, funnily, is actually less to blame for the collapse of the mall than it is typically blamed for. Of course, the destruction of smaller businesses meant that those businesses wouldn’t be around to take up mall space, either, effectively meaning big-box retailers were running a two-front offense on shopping malls by both making the mall itself unattractive to consumers as well as driving consumers away from the kinds of stores you’d typically find in malls.

Now, what matters is that Walmart doesn’t have everything. So, what’s a good strategy for malls? Simple - provide the stuff you can’t find at Walmart.

How the Opulence of Capitalism Saved the Mall

Ross Park Mall is located just north of Pittsburgh along a large, sprawling stroad, nestled on a hill surrounded by retail development. The mall sports two floors in the inner concourse with 5 anchors. At a quick glance, the only significant differences from Century III Mall is that it’s on a hill north of the city rather than in a valley west of the city. While Century III is abandoned and rotting away, however, Ross Park currently sports a near 100% occupancy across 150 stores and is slated to open a new anchor store in 2024. What’s the difference?

We can find a pretty good clue in the list of stores. In the late 2000s, Century III was reliant on mid-range low-desirability brands like Aeropostale, American Eagle, Old Navy, and Lane Bryant. Ross Park, conversely, sports a large amount of popular, largely designer brands like H&M (who has an anchor space), Burberry, Coach, GUCCI, L.L. Bean, lululemon, and Vera Bradley, alongside brands that are popular among younger demographics that would otherwise be less likely to visit a mall but you’re not likely to find elsewhere, like Apple, Vans, Sephora, and LEGO3.

These stores are not convenient. But for brands like this, that doesn’t matter. These are brands that are popular and have loyalty among the American consumer for one reason - they either are or are pretending to be luxury brands. And this is where we meet the other major staple of American capitalism at play here - your average American loves nothing more than looking rich and projecting opulence. There’s a million pieces of supporting evidence I can point to here, but I believe you fine readers deserve better than to be shown the photo of Donald Trump in the room decked out in shitty gold plating again.

The model employed by Ross Park is not a unique one - indeed, most major mall real estate companies have adopted it, including Simon Property Group, the largest mall owner in the US, as well as Westfield, the most valuable mall owner in the US. These malls are all doing more than sustainable business, with many of them definitely thriving - particularly ones close to urban areas with transit connections, which describes the model used for all of Westfield’s shopping centres. These malls, i.e. the ones that made themselves into a destination rather than a convenience, are unsurprisingly the ones that are going to stick around well into the future.

Less good for the shopping mall in general, however, is that out of over 2,500 that existed at their peak in the 80s, we are down to under 700 now - and that includes a large number that are dying and will be out of business by the end of the decade. Nick Egelanian, president of retail consulting firm SiteWorks, predicts that by 2032, we will be down to 100 malls left, though that estimate seems a bit clouded by the immediate effects of the pandemic, and indeed, research firm Coresight Research found that mall traffic and revenue were both up over pre-pandemic levels by Q1 2023.

Malls will still probably be around for a while, but with brands like Crate&Barrel instead of the Toys’R’Us locations you grew up with. They remain a leech on their local residents, to some degree, and will never be able to shake the legacy of racism that forged their existence 70 years ago.

How Stupid Decisions Doomed Malls (just this one mall, in this case): An Addendum

Now, we can talk all day about malls that were run well and malls that were doomed due to lack of change, but I want to focus on a few that were stupid decisions from day one. Well, one, specifically, which was a microcosm of many other stupid decisions.

Malls were being built on a regular basis in America all throughout the 90s into the 2000s - but it was clear by the mid 00s that we should probably stop building so many of these, because these newer malls are never going to work out. And, indeed, 2006 was the last year that any full-size enclosed malls were built in the United States, and no more would be built until after the recession, in 2010 (when Rego Center opened in Queens). The last indoor mall built pre-2008 was The Mall at Turtle Creek in Jonesboro, Arkansas, which closed in 2020, albeit because a tornado ripped through the centre of it rather than any retail-related reasons.

The year prior to that mall opening, however, the Mills Corporation (a mall holding company later purchased by Simon) opened the Galleria at Pittsburgh Mills, also north of Pittsburgh in Frazer Township. This whole project was, frankly, a bizarre choice, and was even covered as such in the contemporary press. Frazier was a largely rural township not easily accessible from any major highways, and the only road artery to it - route 28 - involved driving all the way east out of Pittsburgh before actually going north. It would essentially take you a half hour to get from Pittsburgh to Pittsburgh Mills without traffic, compared to 25 minutes for Century III and 15 for Ross Park - and, more importantly, a grand total of fuck-all people lived in the area immediately around it. Frazer Township is so small, in fact, that the township moved their municipal offices and police department to the inside of the mall, where it still is today.

The entire concept was rather confused from the start - it featured little in the way of upscale retailers, but was clearly trying to compete with Ross Park and touted amenities like a bowling alley (which would be closed by Q3 2006) and a Cinemark IMAX theatre, making it more like the Waterfront in terms of amenities…but still without the stores you’d want to find there. And, again, not located near any actual people. The mall also advertised an upcoming indoor speedway-style attraction with the NASCAR license, which would not only never get built, but indeed, the area where it was to be built is still untouched to this day, including a large section built without a solid outer wall, but just temporary sheetrock that they would have removed once they built the addition.

The mall opened on July 14th, 2005 at under 60% occupancy, which is absolutely unheard of in mall developments at any point in history. In fact, holiday 2005 would actually be the mall’s peak (Sears Grand was not ready when the mall opened, but did open for the holiday season), never breaking 50% occupancy again after the start of 2008. The mall’s largest non-retail occupant was an in-person branch of ITT Technical Institute, if that gives any indication the caliber of business they had to rely on after everything major left in the first 3 years. This would obviously close once the feds rolled up to ITT’s doorstep in 2016.

The 1 million square foot mall has been universally considered one of the deadest malls in America for several years now. In 2017, after it was reposessed by Wells Fargo due to millions of dollars in unpaid liens, the mall sold at auction (to Wells Fargo) for $1004, after having been valued at $190m in 2010 (already less than had cost to build the complex). Today, the mall has two chain retail stores remaining (Bath & Body Works and Macy’s, the latter of which is an anchor with a separate outdoor entrance anyway).

This is all an example of the other, non-societal issue that takes down malls: completely batshit, high-on-their-own-supply management and development teams. Indeed, the Mills Corporation would declare bankruptcy the year after building Pittsburgh Mills after having been investigated by the SEC for their financial incompetence.

The Mills Company did have the sense to sell Pittsburgh Mills in 2006, only a year after having built it, seemingly seeing the writing on the wall. This helped nobody, as the other company involved in developing the mall - who Mills had sold their share in the mall to - also went bankrupt. The mall’s current owner is mall slumlord Namdar Realty, whose failure to pay $11m in taxes nearly caused the mall to go to sheriff’s sale in August 2023.

There was nothing good or smart about this project, from day one to present. It remains a monument to the arrogance of real estate developers.

Epilogue: A Subculture & My Involvement

The term “mallrats” to describe people who hang around malls with their friends without actually shopping has been around since the 1980s. Today, we’ve somehow spawned a community of mallrats who are literally just there to explore dead malls (abandoned or otherwise). I’ve been doing it since 2013. It’s a form of disaster tourism, in a way, but where the disaster is capitalism in and of itself. The photo at the top of the article - Rolling Acres Mall in Akron, Ohio - is a mall pretty similar to Century III, being built as a megaproject in a distant suburb in the 1970s, though Rolling Acres closed in 2008 instead of 2019.

The photo at the top of the article is also, for some reason, my crowning achievement online, having been featured in publications around the globe, including Architectural Digest, Cleveland Scene Magazine, Business Insider(!), and literally countless blogs and info pages in countless languages. None of these sources followed the proper attribution terms under the Creative Commons license I chose when I uploaded the photo, but that’s neither here nor there.

Over the span of about 4 years, I visited the mall numerous times, including one journey into the mall - one where I chose not to take any photos for fear of the criminal penalties of having photographic evidence that I committed trespassing. I’ve done a fair amount of urban exploration since then, but Rolling Acres was my first rodeo, and my second, and my third, etc etc etc. Quite notably, I was an idiot and didn’t wear a respirator during any of these trips - in fact, I didn’t do so at all while urbexing until…probably after I started college. Inhaling a large amount of mold is a bad idea, and given that I also smoked for a period, I am definitely paying the price for fucking up my lungs now. This is 100% on me - I assumed I’d be dead by age 20 and thus didn’t particularly care a bit for my health until around 2019 or so. Consider this my free urbexing advice.

To this day, I have no idea what drew me to retail urban exploration. I’ve been to countless dead or dying malls - including several mentioned here, like Randall Park and Century III for “dead” and Pittsburgh Mills in “dying” - and each one is, to me, as fascinating as the last. Considering what once was there, how wasteful it all seems now in hindsight, and how fragile it all is - both literally and in terms of business - and just how quickly the natural world can reclaim what was once someone’s entire life. And yet, it all comes with a sort of serene feeling of knowing that you’re the only one around in a building meant to house thousands of people. Or hundreds of people, or tens of people, or even less, but it still all feels the same.

Rolling Acres Mall was demolished in 2017, leaving a mostly empty lot. Amazon would acquire the site in 2019 and build a distribution facility there in 2020. There’s a really, really good sandwich place that has homemade chips right down the street that I will go to every 6 months or so.

When I was 16, the very first place I ever got to try makeup on was by myself in the breakroom of an abandoned service station back in my hometown. I’m sure it looked awful, in hindsight, but it was a moment for me that carried probably more emotions than had been felt in that building in the past 20 years. That building is still there, though on the cusp of being redeveloped, and it always brings a smile when I see it.

Every building ever built was built with some specific purpose in mind. Every one was the site of countless human moments, memories, trauma, milestones, anything you could think of, even if the purpose of the building itself was just dull American capitalist consumerism. It’s always something I find myself thinking about, while taking in how little any of these abandoned malls really mattered to the public at large. Somebody, somewhere out there had a specific memory of a date or a breakup or something right on this collapsing balcony I’m currently standing on. Maybe it’s someone I’m connected to, somehow. I’ll never know, because all I can know is being there in the moment.

Does that make it okay for all this to go to waste like it does? No. But it always makes me at least a little emotional, I suppose.

Still open!

Not really relevant, but this is another one of my malls - for those of you that know me, the blue dress came from the JCPenney here.

I swear I’m not shilling I just also happen to like these brands please don’t call me a sellout

This was a choreographed auction, specifically designed for the bank to buy it. Despite this…I mean, the mall did still sell at auction for $100, no matter how many qualifiers you put onto that.