The Death of Apple

How the most valuable brand in the world came moments from extinction, what led us there, and the alternate futures that could have been.

This is a historical retelling of some of the lesser known important events in computing history. It is written for a general audience rather than fellow historians.

In 1986, Steve Jobs was very publicly forced out of Apple, having made fierce enemies out of the entire Board of Directors, including quite famously the CEO he courted, John Sculley. In 1996, he was hired back in exchange for a then-insane amount of money and still-insane amount of control over the company.

The decade in the middle are a period in time the company would rather you forget about. It involves stories of turmoil, both internal and external, stupid ideas, utter failures, missed opportunities, and corporate mismanagement featuring ineptitude on a level unrivaled by any other until today’s Twitter. This is the story of how one of America’s original major tech firms was crushed into irrelevance and mere inches from Chapter 11.

This is the the story of the death of Apple.

June 10th, 1977 was a normal early summer day. In fair Sunnyvale, California, where we lay our scene, it was a somewhat unseasonably cool 62 degrees and partly cloudy.

That morning, computer retailers in southern California, as well as people who had ordered the machine directly from Apple, received the first ever shipments of Apple II home computers1. These machines were rather instantly a hit in the hobbyist space, with built-in support for color and a large amount of internal expansion. In the ensuing years, the Apple II and its derivatives would prove to be a winner in any market segment that could make use of it - most importantly in the home and in schools, where you could plug it in and be up and running in 15 minutes (as long as you had also purchased whatever software you needed). It did have a pricetag much steeper than most contemporary examples, $1,295 compared to around $600 for machines like the Commodore PET, but the ease of use and the color capability made it a hit regardless.

The Apple II’s runaway success set Apple up for a massive boom, rocketing them to the forefront of the home computing revolution. The most prevalent praise the machine got was describing it as the first “appliance computer”, a term explained by BYTE Magazine’s Carl Hemers in April 1977:

The Apple-ll, which is to be introduced in April at the first West Coast Computer Faire in San Francisco, may be the first product to fully qualify as the "appliance computer." An "appliance computer" is by definition a completed system which is purchased off the retail shelf, taken home, plugged in and used.

Creating a computer that met this definition was the vision that both Jobs and Wozniak had in mind from the Apple II’s nascence. The idea that the machine would also be a hit with hobbyists due to its’ expandability, however, was quite famously the vision of Steve Wozniak alone.

The Apple II was succeeded by the Apple II Plus in 1979, which made some minor hardware upgrades and major software upgrades. This was intially intended to be the end of the Apple II line, as starting in 1978, development had begun on the machine intended to replace it.

First Flirtations with Failure

In the second half of 1978, Apple began developing the machine to replace the Apple II - the Apple ///. The development of this machine was different from previous machines in pretty much every sense. Quoting Wozniak’s 2006 autobiography:

“[The Apple /// was] not developed by a single engineer or a couple of engineers working together. It was developed by committee, by the marketing department.”

Heading this committee was Steve Jobs. His persistence during the development phase created a very unique computer that was intentionally big on aesthetics, as well as being big on computing power. One thing it wasn’t big on was cooling - the machine was, at Jobs’s insistence, fanless and ventless, instead being cooled by a solid metal case that served as a heatsink.

Announced on May 19th, 1980, at the National Computer Conference, the machines being shown at the conference were still wire-wrapped prototypes as the motherboard design had not been finished. The machine’s OS, the Sophisticated Operating System (“Apple SOS” - pronounced like applesauce), was still in beta. The announced ship date was June - less than a month away. This was not met.

By July 1980 - at which point a new ship date was still not announced - Apple had pretty drastically changed their tone on what this machine was. Steve Jobs gave a quote to BYTE Magazine:

“The Apple III was conceived primarily to fill in gaps in the Apple II. It will not replace the Apple II by any means."

The Apple /// launched in November 1980. By October of 1981, problems were so numerous that Apple had recalled all of the first 14,000 units in order to install a revised motherboard. The most notable issue to plague the machine’s reputation was quicly apparent - the computer had a tendency to cook itself.

Remember the lack of a fan or cooling vents? The metal case did not effectively dissipate heat, and contemporary reports theorize that the repeated cycles of heating and cooling from turning the machine on and off in daily use would cause the chips to creep out of their sockets, disconnecting from the motherboard. This led to the oft-repeated legend that Apple support would tell users to lift the front of the computer six inches and then drop it back down on the desk, reseating the chips. (As far as I know, this has never been substantiated).

After fixing every customer’s machine, the computer was reintroduced to the market with a revised motherboard in November 1981. They would sell around 70,000 total units until November 1983, when the FCC found that both the original and revised models violated their regulations.

Despite the machine’s mounting failures, both financially and literally, they would introduce the Apple /// Plus, which sold around 40,000 units until it was discontinued on April 14th, 1984. In 1985, Jobs described the /// by saying Apple had lost “infinite, incalcuable amounts of money” on it. Most unsold Apple ///s were sold to computer refurbisher Sun Remarketing, where you could buy them for increasingly cheap.

The Apple ///’s only year on the market without turmoil was 1982. That same year, Apple sold 1 million Apple IIs.

Point-and-Click

In 1979, Steve Jobs visited Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) and was enthralled by the Xerox Alto - a $32,000 computer with a mouse-based graphic user interface introduced in 1973. Shortly thereafter, he negotiated a deal with Xerox to let a new Apple product development team spend two days with the Alto and the Alto’s development and design teams.

The project - known as the Lisa project, after Jobs’s daughter Lisa Brennan - was initially started as a project to modernize the Apple II, but after Jobs effectively took the reigns of the project, it developed into a next-generation GUI-based workstation. The GUI was actually the first part of the product designed, as the hardware was developed around the concept the Lisa team had come up with. The result was a very technologically impressive computer - indeed, actually too technologically impressive, as the Lisa operating system ran rather sluggish on even the high-end Motorola 68000 processor. Lisa OS introduced concepts that we now use and interact with on a daily basis, including the concept of a document-based workflow. Combining the relative sluggishness of the hardware with the machine’s high price tag - $9,995 for the base model at launch - as well as the system’s incompatibility with existing software essentially meant it was doomed even before it launched in January 1983.

Not helping was Steve Jobs, whose continuous insistence on microscopic changes to the GUI eventually got him kicked off the project team entirely in 1982. He would then take over a different project team working on a similar project, essentially forcing the company into competition with itself.

Despite a major revision in 1984 with the Lisa 2 bringing the cost down from $10k to $4k, the Lisa never took off to any major extent, selling only around 10,000 units before being discontinued in 1986.

After selling most unsold machines to a wholesaler, Apple would later bury 2,700 brand new Lisas in a Utah landfill to claim a tax writeoff.

Third Try’s a Charm

With two Steve Jobs-flavored flops under their belts, Apple’s management seemed rather content to just continue updating the Apple II. Indeed, the Apple //e had just launched in January 1983 and had proven an absolute smash hit - even Apple II Plus owners were dropping $1,400 to upgrade to the new machine.

Jobs wasn’t done yet, though. In 1981, his attention was caught by the Macintosh team, who were working on a low-cost appliance computer much like the Apple II that they had designed considering the idea of integrating a more efficient Lisa-like GUI. The project was originally led by engineer Jef Raskin and Steve Wozniak, but Wozniak had been on leave from the company after crashing his personal Beechcraft Bonanza, and something of a power vacuum existed that allowed Jobs to take over the project and claim it as his own. To be clear, that’s now three projects he was simultaneously heading - the Apple ///, the Lisa, and the Macintosh. The Apple /// would crash and burn and he would be kicked off the Lisa team by 1982, leaving him with just the Macintosh - particularly after he also forced out Jef Raskin, making it 100% his.

The resulting product was one that was underpowered and overpriced, with zero options for internal expansion. The machine’s original intended price point was $1,000, but hardware upgrades necessitated by things Jobs wanted eventually brought the pricetag up to $2,495. One major issue was that amount of RAM had been cut to 128k in order to meet that $1k price point, but it remained at 128k despite the increase in price. Apple already had the successor model - the Macintosh 512k - already in the pipeline and entirely completed on a hardware level. The machine also had no fan, and although it did have vents this time, it still had cooling-related failures - just not universal ones this time.

The Macintosh was designed to be a computer appliance, and that was a job it succeeded at - it just turns out nobody in 1984 was quite looking for one that simple and restricted, especially with no backwards compatibility.

It certainly turned a lot of heads, though. You know why?

That fucking commercial.

Often considered one of the most iconic advertisements of all time, Ridley Scott’s 1984 represented Jobs’s metaphorical vision of the Macintosh, and what it represented in the personal computer war against IBM and the PC. (Make commentary on the modern state of Apple however you wish.)

The Macintosh got off to a roaring start, selling 72,000 units in the first 100 days on the market - 22,000 more than Jobs’s very rosy sales predictions. This number was actually constrained to some degree by the speed they could make the computers - they were often on backorder. This did not last. By the end of 1984, they were selling less than 10,000 units per month, and to make matters worse, after the initial sales boom they had ramped up production capacity - a move that was extremely costly and left Apple with a large unsold stock of 128k machines, especially after the 512k model launched in September 1984 and immediately dashed 128k sales to nearly zero.

Once 1985 rolled around, the struggles of the Macintosh were clear. To the Apple board, this was Jobs’s third strike, and in May, the board signed off on a plan to reorganize the Macintosh division, pulling Jobs off the project (again, yes), and in charge of an unnamed, unspecified new product. Unlike the last three times it happened, this one wasn’t an actual product - indeed, the plan was basically to squirrel him away from anywhere he could do actual harm to the company, as CEO John Sculley aimed to bring Apple from the brink of unprofitability by investing money back into the Apple II division and sharply cutting the Macintosh division. Jobs, in what can be only described as “trademark form” at this point, formulated a plan to oust Sculley and take the CEO’s chair. This plan was quickly leaked, at which point Jobs offered to tender his resignation, which the board rejected, while continuing to shuffle him onto the sidelines.

Side ramble: This included a brief stint where Apple was sending Jobs around the world to try and make foreign sales/distribution deals - including a Paris computer show, where then-VP Bush reportedly encouraged Jobs to take his company’s computers right to the heart of the Soviet Union to “forment revolution from below”. The thing is - he actually did try to do this. Jobs went to Moscow in the summer of 1985, where he got in an argument with an American embassy attache over export controls and ticked off his Russian handler by talking about Leon Trotsky too much - specifically praising him in a speech to computer science students at the Russian Academy of Science. (This was not included in the version of the speech released to the public, but has been corroborated by attendees).

On September 17th, 1985, Jobs tendered his resignation to the board of directors of Apple.

Business As Usual

Jobs was replaced in Apple’s management structure by Jean-Louis Gassée. The company immediately began reorganizing internal structures and retooling product lines - in fact, several products had been in development in secrecy to keep them away from Jobs’s influence. These included the Macintosh II and Macintosh SE - the first ever Mac models to have expansion slots, with the SE being the first to have an internal fan and the II being the first to support color. These products - with the II’s color and expansion slots being a huge step for the Mac - made it to market in March 1987. Partnerships with software companies like Adobe and Claris gave the Mac its first real niche - desktop publishing and graphic design. Sales of these new Macs picked up pretty quickly, and suddenly it looked as if the post-Jobs Apple had managed to stabilize the two product lines it continued to maintain, with the two failed product lines having been unceremoniously killed in the preceding years.

In mid-1986, Apple introduced the Apple IIGS - the final improvement on the Apple II line, this was a computer with a 16-bit CPU and sported a color graphical user interface rather than the classic command line of previous Apple II models.

So, wait - Apple had two different products on the market simultaneously that filled the same market niche (home appliance computer based around a GUI operating system). While the IIGS was cheaper than the lowest end Mac of the time ($999 vs $1,500), it does seem like Apple had made a product competing against itself that probably confused consumers to some degree and cannibalized their own sales.

Folks - get comfortable, because we will be hearing this a lot from this point forth.

After several years existing in the high-end space with mid-range options mostly consisting of outdated models - the Macintosh Plus, introduced in 1986 and being a slightly upgraded version of the original 1984 Macintosh, was on the market until 1990 - Apple introduced multiple explicitly low-end Mac models for the first time, specifically the Macintosh LC (“low-cost color”) and the Macintosh Classic - the Classic also being the first ever Mac to finally hit that $999 price point they had wanted for the original Macintosh. They would follow this in 1991 with the Macintosh Classic II as a higher end version of it.

In 1992, Apple introduced their first new product line for the Macintosh - the Performa line of machines. The Performa 200 was an all-in-one like the classic Macs, the Performa 400 was a mid-range desktop, and the Performa 600 was the highest end option. The thing that was most notable about these machines is that they were all rebadged versions of pre-existing Mac models - the Performa 200 was a rebadged Classic II, the 400 was a rebadged LC II, and the 600 was a rebadged Macintosh IIvx. So, they discontinued those models, right?

They did not. The Classic II would be on the market until September 1993. The Performa 200 was sold at $1,295, while the Classic II was $1,900. These are the exact same machine, being produced at the exact same time, with the only differences being software - the Performa coming with more included software - and a $600 lower price tag. These machines were sold simultaneously, in the same stores, effectively competing against each other despite their similarities. The 400 and 600 were the exact same situation, though the LC II was often sold with an Apple IIe Card2 and the 400 was not.

Two identical models wasn’t even close to the worst of it. Visible here is just one example of technically identical computers being sold with different model numbers simply because they came with slightly different software packages:

This pretty quickly served to alienate retailers and confuse consumers - and this was the overarching theme of 90s Apple. I could go on and on with examples for paragraphs and paragraphs, but ultimately, model creep was the first thing that started to mark the rot that was slowly killing the company.

Behind the scenes, the company was making all sorts of moves, ones that made sense and ones that didn’t. The most significant one was joining the AIM Alliance - a corporate alliance of Apple, IBM, and Motorola in order to develop a new computing platform, which would eventually turn into the PowerPC family of processors that would serve as the backbone of the Macintosh family until 2004.

Behind the scenes during the formation of that alliance, in 1993, IBM would make an offer to buy Apple for an amount reportedly around $40/share. A few years later, Apple would approach IBM and ask if they were still offering this. Their response has been lost to time - all of this comes from the account of board member Mike Markkula. Presumably both IBM and Apple would have preferred to never think about it again. IBM would instead acquire software company Lotus.

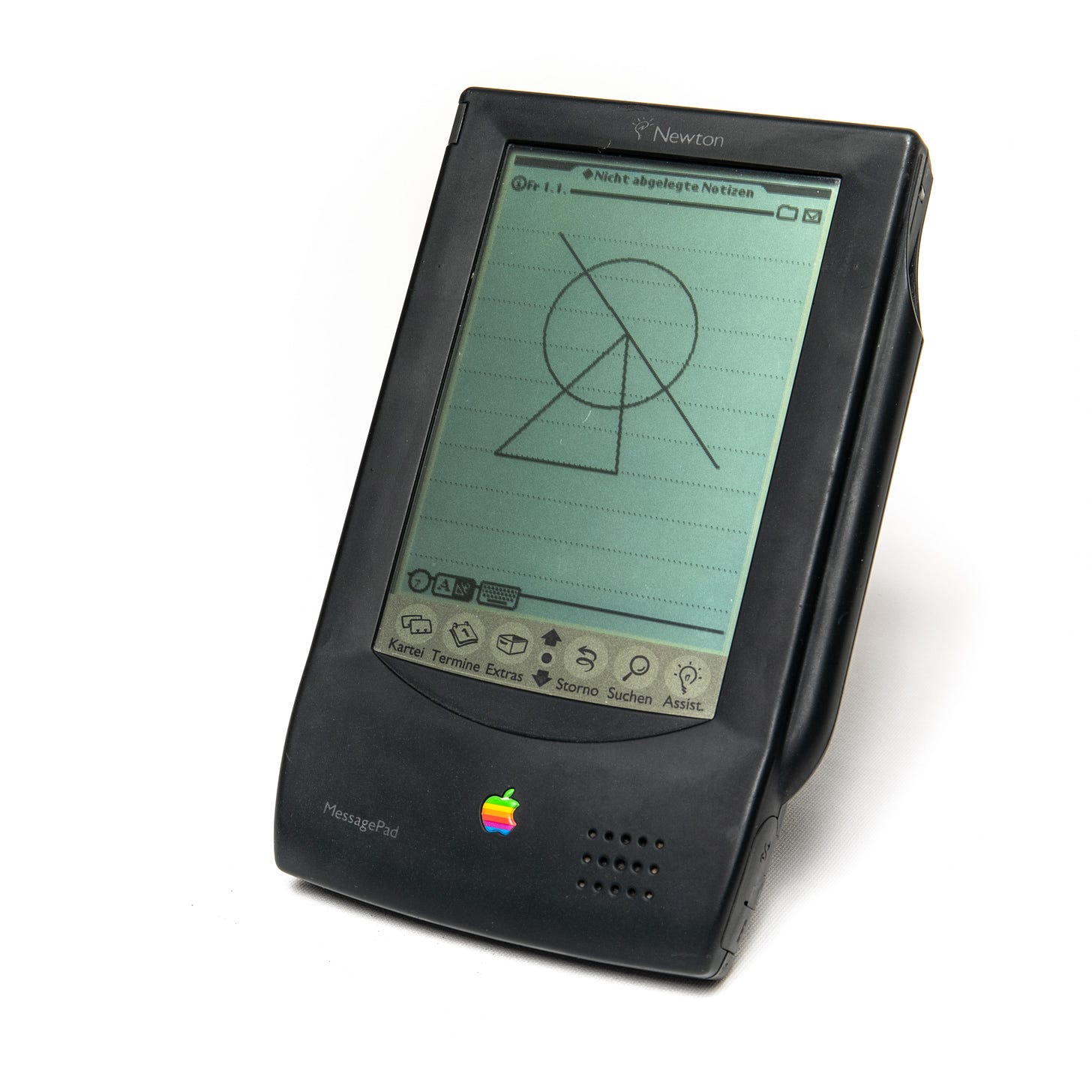

Also in 1993, Apple introduced a product that had been in development for years - the pet project of CEO John Sculley, who actually coined the phrase “personal digital assistant” to refer to it - the Apple Newton MessagePad.

A Portfolio of Lead Balloons

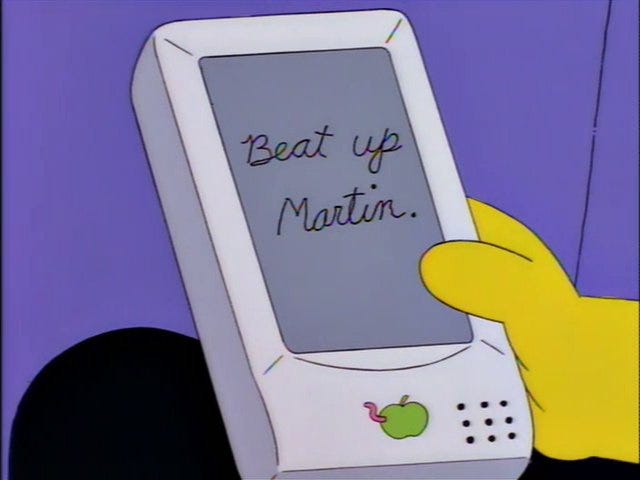

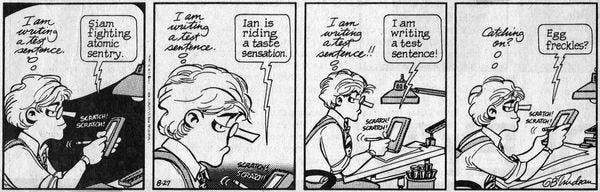

The Newton is the device that is universally mocked nowadays as a sign of the sort of weird stuff Apple was getting into in the early and mid 90s. In truth, the Newton was a device ahead of its time - not only in the sense of “why would any consumer want this in 1993”, but also that the technology required to really support such a concept was just not where it needed to be. The device was sluggish, it’s killer feature - digital handwriting recognition - was so faulty it was universally mocked, and the original MessagePad’s price tag of $699 was widely considered unspeakably ridiculous. The AAA batteries gave it a short battery life, and connectivity with a computer was limited (initially Macintosh only).

The device was pretty widely ridiculed in the press, mocked in popular culture, and quickly revealed itself to be a financial flop for Apple.

Apple had invested $100m in the development of the Newton and was, from the start, essentially doomed to never turn a profit from it, and by the time the model line was discontinued in 1998, they had sold around 200,000 Newtons total.

In a company that was already struggling from declining sales of the Macintosh, essentially setting $100 million dollars on fire was obviously going to require a fall guy or two. As you might expect, CEO John Sculley was forced out on October 15th, 1993, and replaced with Chief Operating Officer Michael Spindler.

Sculley’s tenure at Apple was over, but not without a bizarre footnote - according to a July 1992 article from the Los Angeles Times, Sculley’s name had been floated by Bill Clinton himself in meetings as a potential choice for Vice President, as “a businessman who could blunt some of Ross Perot’s independent appeal”. This went nowhere, though Sculley did develop a friendship with the First Lady in the process.

Spindler, while CEO, oversaw a huge amount of cuts - including in workforce size, executive pay, and overall R&D projects - but it did not quite lead to the kind of turnaround that Apple needed. Alongside continuing to develop the Newton line, Apple would also branch out into a few other market segments, none successfully.

In 1994, they released the QuickTake 100, the first consumer digital camera. This was also a massive technical feat that nobody at the time asked for. At $750, it wasn’t quite going to break through to the average point-and-shoot photographer, but the quality of the images it produced was not exactly anywhere near the caliber of quality for a professional photographer. They would release three models before discontinuing the line in 1997.

Also in 1994, Apple began development on the Apple Interactive Television Box. This was designed to be an interactive set-top box to interface between a user and a cable/satellite/television service, much like the modern concept of a cable box (and not particularly far off from the idea behind the modern Apple TV). In terms of hardware, this was essentially just a Macintosh LC 475 with a special ROM to boot from a network server. Despite being test marketed in numbers upwards of 5,000 - including in hotels at Disneyland as well as a cable system run by British Telecom - the device was never officially released. They pop up for sale occasionally online, but are mostly useless paperweights, excluding a few development units that can boot from external SCSI hard drives.

Yet again in 1994, Japanese video game company Bandai approached Apple to gauge their interest in partnering to develop a video game console, with Apple developing the hardware - based on the Macintosh platform - and Bandai handling the marketing side of things. Apple would develop the Pippin and Bandai would release it in Japan in December 1994 to a resounding “meh” from the gaming community. There was essentially no interest in a neutered Macintosh you hooked up to your TV and controlled with a trackball and a controller that looked like the PlayStation 3 boomerang prototype. Apple had designed the Pippin to be an open platform, a technology licensed by anyone who would like to build a console around it. Only two companies - Bandai and katzMedia - would ever do so, releasing a total of 61 games for the system, almost all just standard Mac games ported to the system. It would be killed off by 1994, selling a whopping 42,000 units worldwide. This is usually considered Apple’s biggest failure of all time, though technically speaking, Apple wasn’t really selling anything, just licensing the technology.

Financial & Technological Selfcest

One of the biggest proposals designed to bring in income during the darkest days at Apple was the Macintosh clone program. Much as Microsoft had taken over the market by licensing their operating system to other PC manufacturers, Apple saw some value in selling licenses to sell third party computers with the Macintosh ROM and Mac OS, as long as those licensees paid an initial fee, as well as a fee of $50 per computer sold. This would come to pass in early 1995, with 30 companies licensing the Macintosh technology to sell personal computers of their own. In some cases, companies could actually license generic motherboard designs to implement into their machines.

This ended up proving a bit shortsighted. Companies not having to price the development and engineering of the OS into the final product (since they hadn’t developed or engineered it) meant that they could undercut Apple by increasingly large margins, which they happily did - and, indeed, with Apple willing to license them a motherboard design, they didn’t even have to pay hardware engineers. Clone manufacturers could sell an end user a machine that was more powerful than a high end Mac for a much lower cost - a deal users were more than happy to take. In essence, we had Apple not just competing with themselves, but instead opening a whole new market to allow other companies to compete with them on their dime. Licensing deals, as negotiated by Apple management, were super friendly to the clone manufacturers, meaning that Apple saw surprisingly little money, considering the circumstances.

Clone manufacturers would also do previously unseen stuff with their Macs - Power Computing shipped the first Macs with multiple processors, allowing them to double (and, in the case of one model, even quadruple) the speed of the highest end Mac.

The clone project would be terminated in 1997, with all licensing deals ended by the end of that year. It’s not really possible to know for sure how much money Apple lost with the project, but every clone sold was a Mac not sold, a number that added up pretty quickly. The project had succeeded in increasing Macintosh market share - up to 10% from being under 4% several years prior - something which brought with it no helpful increase in revenue. After the program was terminated, Apple would buy the largest clone manufacturer, Power Computing, for $100m.

Into The Great Wide Copland

One of the biggest problems plaguing Apple is that the Mac OS, the operating system that formed the backbone of almost all of their hardware products, was, under the hood, the same piece of software that had shipped with the Macintosh 128k in 1984, with new features and extensions just tacked on top. This had a side effect of making it phenomenal for compatibility - an application from 1984 will likely run fine on a machine running 1999’s Mac OS 9 - but also meant it was slow, insanely easy to crash, and often destructive when it crashed, as well as lacking basic concepts like protected memory, multiple users, and, indeed, even multitasking. It needed replaced, and in 1994, the company conscripted their most experienced engineers to work on the replacement: Mac OS 8, codenamed Copland. This would be their vehicle into the 21st century of computing and what their computing platform would be based on for the foreseeable future.

The team’s job was to deliver on a feature-rich OS full of all the technologies that the classic Mac OS both already had and sorely needed. The problem? Well, let’s take a look back at the patterns here. Model creep in the Macintosh product line, and feature creep in the Mac OS and Lisa OS more than a decade prior. Was Copland bound to fall victim to feature creep yet again?

Yeah. It was.

Apple would announce Copland in May 1994, with a demonstration of certain new technologies at the 1995 Worldwide Developers Conference - along with a ship date of early 1996 for the finished product, and late 1995 for a beta. After a flurry of press over the summer, including a report that Copland would support running Windows applications (that was immediately confirmed by multiple engineers and then simultaneously denied by several other engineers), eventually everyone realized that they hadn’t so much as seen a screenshot of a beta release.

Indeed, late 1995 would go by without so much as a peep about the OS from Apple themselves. Management was, at this point, relatively resigned to letting the ship sink and stripping it for valuables on the way out - Spindler and company had been in merger talks with Philips and IBM (as mentioned above), as well as a notable buyout deal with Sun Microsystems that made it into the 11th hour before being called off (it’s not 100% clear who called it off, but considering the overall state of Apple, it seems safe to guess that was Sun). This period of time was also when the Macintosh clone project began, as mentioned above. In November 1995, they would ship Copland “Developer Release 0” to a very few specific developers, which was so unstable that it essentially couldn’t be used for development and had very little of the functionality of classic Mac OS built into it yet.

In early 1996, it was evident yet again that things weren’t quite going to plan. After those merger deals all collapsed, CEO Michael Spindler resigned on February 2nd, replaced by National Semiconductor CEO Gil Amelio.

With a third CEO in under five years, Amelio’s job was to consolidate Apple down to as small of an operation as possible to bring it to profitability, and to create a future for the company by getting Copland back on track.

Amelio would take the stage at WWDC 1996 to demo various things about Copland, sell people on the live demo sessions on the convention floor, and provide a ship date of late 1996. Developers were stunned to find out at those demo sessions just how undeveloped Copland really was - indeed, the OS didn’t even support text input at this point, and was supposed to ship in just a few months.

In June 1996, Amelio would hire his chief technology officer from National Semiconductor, Ellen Hancock, to take engineering by the reigns and get Copland back on track for a release slated for 1997 at this point. By August 1997, it was clear to Hancock that Copland was absolutely cooked and unmanageable, and Amelio would formally cancel the project, leaving Apple with no sustainable profit, a microscopic userbase that was only growing due to a clone project that was losing Apple money, and, indeed, no future roadmap to speak of.

Amelio would, at this point, begin to prepare Apple to be sold off to a technology firm, beginning negotiations with Sun Microsystems (again!), while also engaging in an absolute last ditch plan to bail out the company: acquire a new OS from outside the company.

Failed Deals with the Devil

With the end of the line seeming inevitable, Amelio and the Apple board began discussing what options they had to acquire an outside company and repurpose their pre-existing operating system for the needs required by Mac OS. The list of candidates was simple:

Sun Microsystems’ Solaris. At the time, in version 2.5.1, Solaris had just recently been updated to support the PowerPC architecture, making it a big contender. As an OS largely limited to enterprise settings, however, there was essentially no base of existing applications, and the default desktop environment (OpenWindows) was relatively primitive and featureless.

Microsoft’s Windows NT. No, really. This was Gil Amelio’s preference, in fact, having had brief conversations with Bill Gates about if his engineers would be up for porting specific Apple technologies to NT. Indeed, Windows NT 4.0 had also added PowerPC support around this point. The main issue here is that it was Windows, and Apple acquiring and retooling Windows seems like it would just cause their userbase to switch to PC.

Be Incorporated’s BeOS. BeOS was a minor contender in the OS world, but had several advantages over other candidates - Be was started by former Apple exec Jean-Louis Gassée and was already designed not only to run on PowerPC, but on existing Mac hardware, too. BeOS was also multimedia oriented, which also made it a good fit for the Mac ecosystem. The primary issue was that BeOS was basically half-baked and was missing many basic features, including things like printer support.

NeXT Computer’s NeXTSTEP. The Unix-based OS from the company Steve Jobs founded after being forced out of Apple. Unlike the others, NeXTSTEP had no PowerPC support.

By this point, it was evident that the clock was ticking - and fast. With Sun basically entirely uninterested in dealing with Apple at all, including buying them out or selling them Solaris, they knew they were on their own, so they essentially had to figure it out before the beginning of 1997. Amelio was talked out of the “buy Windows and make it into Mac OS” idea. We’re not sure who did it or how, and it’s not like Microsoft would ever realistically have sold it to them, but we can be thankful that they did.

With the contenders whittled down to Be and NeXT - both second-tier companies in the tech space at this point anyway - it really came down to questions of expedience. Reportedly, after Amelio was pleased with a demo of BeOS, he was very much a fan of it, inviting the board of Be to submit an offer, which Amelio expected to be in the range of $50 million, taking into account factors like the beta state of the software.

Gassée came back with a proposed price of $350 million.

Left with an insanely sour taste in their mouths, Amelio and Apple execs would then meet with NeXT executives for the same reason. NeXTSTEP was a finished OS (and had just released a beta for version 4.2 in September). NeXT had also developed WebObjects, a highly advanced web application framework. Their CEO was also Steve Jobs, which in and of itself was a weighty factor on the decision.

On December 20th, 1996, in an announcement that the public did not at all expect, Apple Computer announced their acquisition of NeXT Software in a $427 million deal that consisted of cash, as well as a significant amount of debt and 1.5 million shares of Apple stock. NeXT CEO Steve Jobs would be retained as a consultant for Apple.

The nightmare was not quite over yet, however. Apple’s CFO obtained a line of credit from the banks that would allow them to operate in the short term, but they still had to turn things around fast. Amelio was, at this point, widely seen as bumbling and ineffective as CEO - something which showed in the stock price, which continued to tumble down throughout 1997, hitting a 12 year low in June 1998. On June 26th, an anonymous shareholder3 dumped 1.5 million Apple shares in what was widely seen as a vote of no confidence in Amelio, dragging the stock price to a near all time low. By this point, Apple’s cash reserves and lines of credit were to a point that the company had enough capital to survive for around 90 days and no further.

Over the July 4th weekend, Jobs planned and executed a coup, effectively finishing the job he had failed to do against John Sculley 11 years prior, and Amelio would resign on the 9th. The act of ousting Amelio was enough on its’ own to convince the banks to extend larger lines of credit, giving the company a bit more time. In the 1997 fiscal year, Apple had lost $1.03b.

On September 16th, 1997, Steve Jobs was appointed interim CEO of Apple Computer, Inc. Jobs would go on an immediate hack-and-slash of the company, slimming it down as much as humanly possible. Immediately gone were all the consumer product lines (including the Newton, which Jobs infamously hated because of the stylus), removing 70% of Apple’s total product offerings, and with them went 3,000 jobs. Jobs also negotiated a $150m investment from Microsoft and formally killed the Mac clone project.

By the time the 1997-98 fiscal year began, Jobs had already set up the product line to foster success - the Performa line was eliminated and the Power Macintosh line was slimmed down to two models, both with the same specs but serving different utilities (the Power Macintosh G3 desktop, which sat under your monitor, and the G3 tower, which offered more expandability). The portable line had been slimmed down to just the single PowerBook G34. This had all been done by the end of November 1997.

With the professional product line largely straightened out to the bare basics, Jobs had set his eye on doing one thing: developing an all-purpose “appliance computer” that any consumer could take home, plug in, and get online with in under 20 minutes, at a price point under $1,500, that stood out as a piece of furniture in your living room rather than a generic beige box. This, as he thought, would be the puzzle piece to return Apple to profitability.

On May 6th, 1998, Jobs would introduce Apple’s new consumer machine - the iMac G3. The compact all-in-one in a seafoam green-like color was what the company had to rely on if they wanted to have a successful future. The computer would hit store shelves in early August 1998.

By the middle of January 1999, four months after it was introduced, sales figures indicated Apple had sold 800,000 of the machines, making it the best-selling computer on the market at the time and the best selling computer in Apple’s history. These sales figures meant that Apple had clawed back most of the market share it had lost from killing the clone program, but this time it was actually their computers. By the end of the 1999 fiscal year, Apple would report a net profit of $309m - a rather stark contrast to the $1 billion loss the year before, and most of it coming from a single kind of computer that was on the market for slightly over a year.

In April 2001, Apple shipped the one millionth iMac G3, which would solidify the machine as the 6th best selling computer of all time, and the best selling post-internet computer of all time, both titles it still holds.

There were a lot of reasons for the iMac to be as successful as it was. My personal guess as to the biggest factor, though?

This time, it came with a fan.

After introducing the machine at the West Coast Computer Faire on April 16th of 1977, Apple had sold a number of bare motherboards to hobbyists - caseless, power supply-less, and keyboardless, much like 1976’s Apple I. These were delivered as early as May.

The Apple IIe Card was an add-on for the Macintosh LC II computers that was effectively a whole Apple IIe that you could access from within Mac OS. This was designed for education markets as a solution for the recently discontinued Apple IIe (and Apple II in general).

See previous paragraph.

The PowerBook 2400c remained on sale in Japan until April 1998.

This was a great read, fascinating and well written history! I look forward to seeing your next work!