Killing a Century-Old Public Service in the Name of Progress

An abridged version of this article appeared in 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, Spring 2025, as "Meditations on Societal Collapse (Via Payphone)". This is the unedited version, written in August 2024.

Back at the beginning of 2024, I was really interested in getting landline telephone service to my apartment. As I was interested in experimenting with dial-up internet and fax, I was intentionally looking for legacy POTS line (plain-old telephone service, the common moniker for a normal, old-fashioned phone line) rather than a VoIP line (voice over IP, basically telephone over the Internet, commonly branded as “digital phone”), which is far and above the most common thing you get offered nowadays. So, I initially called the local corporate successor to Bell - Verizon. After they tried to sell me on a VoIP line, they eventually connected me to a level 2 tech, who told me oh, yeah, our maps are telling me we haven’t served your apartment since at least 2019. Not surprising, but annoying - particularly given the phone jacks affixed to my walls.

I did have one hope left - the local “independent” telephone company, which did have jurisdiction over some telephone lines - some company I had never heard of called Brightspeed. After pleading for a standard, POTS line, they said they could do it. I asked a question that I knew would reveal whether or not it was actually POTS - “does this work if the power goes out?”. Telephone lines, traditionally, are segregated from the standard local power grid, meaning that unless power goes out at the local office, 12 volts will go down the line, and your phones will work.

No, she said, it wouldn’t. Turns out they were just selling me normal VoIP with an analog telephone adapter and telling me it was POTS - and wanted $65/month for it. I said ‘fuck it, I’ll do it myself’, and eventually created my own VoIP-based telephone system that does support fax and dial-up - MayaTel. It’s a rather clunky system, but it works and costs me less than $10/mo.

This is only sort of related to my point. Actually, I want to refocus the same point on a much different scenario. Let’s imagine you are in the downtown area of your local city center. You have been dropped there with absolutely nothing but the clothes on your back - no purse, no pocketbook, no phone, no keys, no change, nothing. You are in trouble. You have to reach someone you trust. You know their phone number, all you need is a phone. Asking to borrow someone’s phone is pretty unlikely to work - we live in a low-trust society these days, after all, and this isn’t gonna fly after some news stories talking about people lending their phones to strangers only to find their bank accounts drained with a slight-of-hand Venmo transaction. What would the cheapest way to buy a cell phone and get it connected to a provider?

The best example I can give for this is to look at Dollar General. I am aware that convenience stores are options, but they are probably likely to be more expensive, and Walmarts aren’t exactly super common in downtown areas. The best deal you’re about to get on a phone is for a Tracfone-branded smartphone for $19.

Now, that’s just for the phone. You need to get service. Tracfone’s cheapest plan is $15/mo.

Quite notably, with these modern Tracfone-branded prepaid phones (along with all prepaid brands offered by both AT&T and Verizon, with Tracfone belonging to the latter), you cannot just connect them to wifi and go about your day - they require service in order to get past setup. These are subsidized devices, you’re getting them at a pretty big discount so you can be locked into a carrier. Ignoring a $19 flip phone without wifi, Dollar General doesn’t sell those, so we’re back to square one.

So, right there, you’re at $34 total for a phone and service - and you’re not going to be signing up for that service without a valid debit/credit card.

Oh, and, of course, you can’t buy a prepaid cell phone at most retailers without a valid ID, either. Looks like this entire thought exercise was pointless from and I’ve just been wasting your time, eh?

Now, to get to my point: what if I told you there was a way to make a phone call in a public place for usually just two quarters, or one dollar for long-distance, or, hell, zero dollars and zero cents if you’re really in a pinch and use a collect calling service? More than that, what if I told you that these were adopted en masse, available pretty much everywhere from office buildings to train stations, and had very little downtime when paired with bare basic regular service and maintenance?

And then what if I told you we pretty much entirely got rid of this solution in favor of the previous one?

You’d probably see where I’m going with this at this point. Ladies and gentlemen: the humble public phone.

Now, I’m sure some of you are thinking that the scenario I’m positing is pretty unlikely. And you’d be right! So, in order for me to make some kind of a case here, let me use a much simpler example - my old, scratched, well-worn iPhone 12.

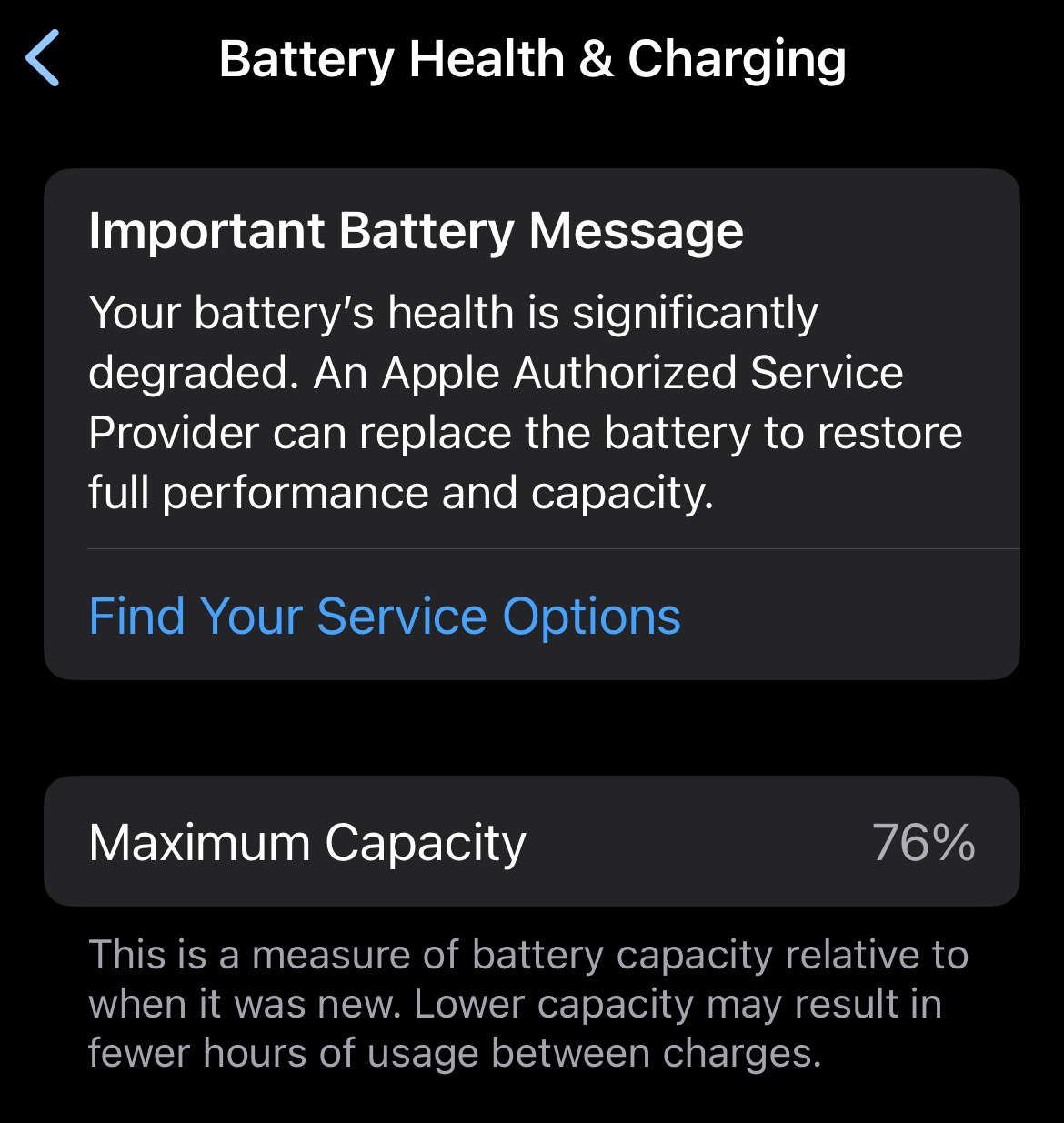

I have absolutely beat the shit out of this phone, and have the battery to match it. It sits at about 2.5 hours of battery life when actively in use. As a result, when I’m out doing full day trips or whatever, particularly when I’m without my car, it’s very often dead. This does lead to trouble, particularly as someone who has a nasty habit of forgetting my wallet and needing to use Apple Pay (plus, it’s where my transit card is). It’s also meant I’ve not been able to reach people I’m picking up from various places, whether something for work, or girlfriends from the Greyhound station. Indeed, it seems reasonable to say that transit hubs are a particularly good case for having public phones on offer - and, actually, some of Pittsburgh’s Light Rail stations still do have them or did have them until recently. You will often find very small banks of individual public phones at airports, as well, almost always equipped with TTY keyboards for hard of hearing folks who need a relay service. I’m not 100% sure why that’s the focus, but in my experience, it’s true in a lot of places, including at rest stops along the Pennsylvania Turnpike and sections of Interstate 80 - major highways being a similarly good use case, particularly for emergencies.

Indeed, I actually want to talk about emergencies specifically for a minute. Once upon a time, there used to be public phones on a lot of street corners, particularly in cities. These were genuinely great for emergency cases - for both bystanders and victims, whether that’s something like a car crash, or just simply being robbed, a scenario where you’re quite likely to not have a phone on you anymore for rather obvious reasons. In the case of ones placed in rest stops along major highways, it’s also a great resource if you’ve simply happened to break down and need to call AAA. When it comes to much more wide-reaching disasters, they play a similar role, as public phones largely continue to operate during blackouts (a fact Verizon used to brag about). Indeed, in terms of localized disasters, after September 11th, Verizon installed over 220 wireless payphones in addition to the 4,000 already installed in downtown Manhattan, and offered free calls to the public through them. Not to say that 9/11s are particularly common these days, but with general weather disasters and large-scale violent acts at all-time highs thanks to climate change and Republicans (respectively), I think it’s a reasonable point, particularly with the recent headlines about Elon Musk’s offer of “free” Starlink internet access in areas affected by Hurricane Helene actually costing upwards of $400 for equipment.

But there’s actually one use case that I want to put a little more focus on, which I started really thinking about after exploring some of the resources available at my local library - people without housing.

This is where the prepaid cell phone pricing I mentioned earlier in my implausible hypothetical comes into a real world scenario. There is a significant population out there that simply can’t afford or access that for one reason or another - cost or lack of necessary documentation. Even as cell phones get more affordable over the years, there’s still a pretty significant barrier for someone with no income, particularly considering being in poverty is also highly correlated with not having access to a current ID. The Carnegie Library system is actually very accommodating towards folks without access to an ID - offering membership to Allegheny County residents pretty much automatically as long as there is an electronic record of them residing there, and accepting pretty much anything with an address on it if you don’t. They also offer career training opportunities, voter registration resources (a voter registration card actually being enough to get library membership, coincidentally) and computer access, on top of being a fee-free library system overall, making the whole library system an extremely good resource for underprivileged folks.

I mention this because one of the things they don’t necessarily offer is access to a phone. Some things need to be taken care of via phone and not the Internet - it’s just the reality of life as we know it, particularly with regard to government assistance programs (the only alternatives there being mail, which is going to be a rather big lift for someone without a permanent address). However, at the CLP Main branch in Oakland has something that really surprised me - an actively maintained payphone (with directional signs pointing to it, even!)

It’s actually fairly reasonably priced as payphones go, too - 50 cent local calls extend beyond the standard 412 (Allegheny County-exclusive) area code and into the 724 area code, covering the vast majority of western Pennsylvania, and $1.00 nationwide long-distance calls (that price point is actually normal, in my experience).

This phone is actually what got me thinking about their potential utility to underprivileged communities - after all, it’s a lot easier to get 2 quarters than it is to pay for a whole phone - as well as the general population at large simply just for convenience and accessibility.

Despite all this, telecom giants - namely AT&T and Verizon, primarily - are pretty gosh darn uninterested in maintaining infrastructure like this, regardless of the societal benefits, because it absolutely is not worth the investment in terms of capital.

Verizon and AT&T are both companies that bring in an annual revenue of over $100 billion, each with a cellular customer base of around 110 million subscribers. Besides their cellular business, they also have significant operations providing home services, specifically internet, television (AT&T specifically owning DirecTV), and digital phone service. (Neither company will easily sell you analog phone access in 2024, and AT&T actively will not sell POTS home phone service to anyone, regardless of how hard they ask, referring to it as a “retired service”.)

Neither Verizon nor AT&T provide a revenue breakdown that details the costs and revenue for POTS telephony anymore. Verizon does not provide numbers for their wireline divisions in general, but AT&T does - revealing that (at least in Q3 2023) their home internet offerings make up essentially all of their wireline service revenue and expenses, representing 13.9 million broadband and DSL internet connections. That DSL figure actually provides some insight into their POTS telephone offerings - AT&T’s DSL is only offered over a POTS line and is incompatible with their digital phone services, which require broadband.

Of the 13.9 million broadband and DSL connections, broadband makes up…13.7 million, while DSL makes up less than 200,000. For context, in that same quarter, AT&T added…311,000 broadband subscribers, more than 50% of their total DSL subscribers. Their business wireline division, which would (theoretically) be responsible for servicing public phones, is similarly almost entirely made up of enterprise internet contracts.

Of course, beyond that, neither Verizon nor AT&T offers public phone installation, service, or maintenance anymore - they only offer connections to the larger phone system, while small, independent companies are responsible for those. However, the situation there is significantly more morally bankrupt than just being standard capital: a lot of public phone servicing companies are subsidizing that sector of their business with revenue from their primary operations - prison inmate telephone services. This includes the company operating the CLP payphone pictured above, which is branded as being serviced by “Legacy Communications, Inc.” in Cypress, California. That company’s full name is Legacy Inmate Communications Inc., d/b/a Legacy Communications Inc. Phone rates for incarcerated folks have received some press in recent years for being unreasonably exorbitant, having been slashed by FCC decree just three months ago. To be overtly cynical, I would expect this to lead to further reductions in existing payphone services, as those increased costs are offloaded onto those still paying for their upkeep.

To reach my ultimate point here, this entire system is just a massive clusterfuck in every organizational regard, and is currently fueled from the worst resource imaginable, human suffering. Verizon and AT&T’s decision to depart from the public phone industry and leave it to these folks (or just literally abandon existing infrastructure) despite it having next to no direct impact on their bottom line is depriving us of a valuable resource in service of an additional half of a decimal point on their annual reports.

There’s actually a very simple solution to all of this that could have been executed during multiple convenient points throughout the 20th century - nationalize the nation’s telephone monopoly, the Bell System. Obviously this is not something that’s going to happen in 2024, not just for political reasons but also because it’d be logistically impossible.

At the same time, though, there’s actually a good example and reason to believe it’d have led to positive outcomes in this specific field. Let’s take a quick trip across the Pacific.

After WWII, the US brought in AT&T and the Bell System to rebuild the communications network of Japan. In 1952, this became a state-owned company known as Nippon Telegraph and Telephone - NTT. (If you’re an American, you might know this name from their slightly bizarre sponsorship of the IndyCar Series.) In 1985, NTT was privatized (with the government retaining a legally-mandated 33% of stock ownership), but they remain legally required to maintain a network of public phones - something they do faithfully, in all parts of Japan, rural and urban, and almost always in full booths.

Unlike American companies, NTT is legally required to release statements breaking down individual sectors of operation, which shows us that in Q2 2024, NTT had a total of 107,336 payphones installed and active across the country. They do not appear to be actively installing more, but are servicing and maintaining them, meaning that the only costs to NTT are personnel costs (and I can’t exactly calculate how much NTT is spending on man-hours to fix public phones) and materials that go into fixing them. According to their 2023 annual report, maintenance makes up less than 7% of their annual expenses of 378.3 billion yen, with the company turning a profit of 64.8 billion yen last year ($459 million, using exchange rates from December 2023). Maintenance across all public facilities - not even just public phones - cost 3.9 billion yen, or $28,000,000, making up significantly less than they spent on sponsorships last year.

Basically: it’s a public service that costs companies pennies on the dollar, and in the US we’ve pretty much entirely gutted it, except for when we fund it by defrauding prisoners. I mean, at this point, what more can I say.

Of course, a fairly reasonable solution would be for the government to subsidize it. This could actually easily fit into an existing government subsidy program - the FCC’s Lifeline Program, which provides internet and cellular access to low-income households, which serves over 8 million households on a budget of $2.385 billion. (To my point, the Lifeline Program is, in most places, only accessible after applying via a convoluted online portal, or via phone.) Notably, that $2.385b budget is already set for a $100m increase in the 2025 federal budget, a number that would certainly cover existing public phone maintenance and upkeep, quite likely twice over.

This isn’t an ideal solution. I’d go as far as to say it sucks, actually, but it generally reflects the state of how we do telco subsidiaries in this country, which is to license it out to a contractor (in the case of the Lifeline Program, that’s the Universal Services Administration Company) who then repeats the same process with subcontractors, and so forth. A better solution would have just been to provide tax credits to the major providers doing upkeep on public phones, i.e. your local telco alongside AT&T or Verizon, but the ship has long sailed on that.

Indeed, that’s what most of this represents - a public service, unfairly painted as obsolete due to significant decreases in usage, totally decimated by major corporations, with every opportunity to save it, whether in recent history or 50 years ago, being a missed one. It sucks for everyone involved, and we’re worse off as a result.

To wrap this up, I don’t think we’re ever going to see a resurgence of public telephones in this country. I simply feel we’ve let go of something useful because corporations told us we didn’t need it anymore.

I’m actually not the only one that thinks this, either - multiple people with access to far more resources than I’d ever have have set up their own independent public phone networks, usually free of charge. This was most famously done by Futel in Portland, Oregon; which itself inspired similar projects like Philtel in Philadelphia and Randtel in Randolph, Vermont (a town of under 5,000!). Futel is continuously expanding, having installed a new phone just on the 24th of September, and even has phones in Seattle and Long Beach, Washington, along with both Detroit and Ypsilanti in Michigan. They offer voicemail and live operator services to any passersby, and they do all of it for free, including calling to most of North America. These operators will occasionally post logs detailing the calls they receive, which is always a fascinating read. They’ve actually gotten large enough and received enough good press and general recognition to receive funding from Regional Arts and Culture Council, a local government-supported nonprofit in Multnomah County.

Futel’s “About” page has an extremely poignant sentence that I think does a good job summarizing my thoughts on our reality, and being a good statement describing what they’re doing to improve it:

Denial of telephony services has long been a tactic used against undesirable populations, and our devices will counteract that. But more importantly, we will help to establish a new era of communication, one in which reaching out is not only desirable, but mandatory.

Ultimately, where the major telephony corporations have utterly failed us at every step and created more issues and more suffering along the way, the same type of folks dedicated to using blue boxes to get free long distance calls from Ma Bell are now the only ones providing any hope that we can counteract that. The community has, once again, stepped in to provide where companies and government have failed, which is awful for society at large - but does, hopefully, make you feel at least a smidgen better about what our little communities can do, even in a low-trust society.